This is the keynote presentation Cologe GameLab asked us the give at the finnisage of the Notgames Fest on 16 August 2011.

Almost 10 years ago, Auriea and I switched from the web to video-games as a medium for our artistic activities. We had already been playing some video-games and they had inspired our work here and there. But somehow it had never occurred to us that we could make them ourselves.

When you come to video-games late, like we did, when you missed Mario, skipped Zelda and can’t distinguish too well between childhood memories of Hide & Seek and Pac-Man, video-games seem like an exciting new medium for artistic creation! In video-games you can make living worlds to explore, you can breathe life into artificial characters, you can set up conditions for situations without knowing how they will play out, you can create a visceral form of visual poetry that makes the separation between the art and the spectator very small. How could our artists’ souls not be attracted to all this potential? Indeed, this medium seemed like a godsend to satisfy centuries of artistic desires. The desire of the artist to become one with the spectator, the desire of the spectator to step into the mysterious world imagined by the artist. It was pretty clear to us: the medium of video-games is the medium mankind had always been waiting for.

As newcomers to a field, we started to investigate our new surroundings. We visited conferences and fairs and played hundreds of video-games. From the most well-known to the plain obscure.

We ended up confused and disappointed. Yes, we did find the worlds and characters and situations and even the poetry that comes so natural to this medium. But we were surprised to find that most video-games were structured in a way that prevented us from engaging with this content. With almost no exceptions, each video-game put obstacles in our way that we needed to overcome. The connection between these obstacles and the fictional world they were placed in was mostly rather vague and often even absurd.

It seemed to us that the things we were interested in -the imaginary world and its fictional characters- only served as visual presentation of an underlying system. This would explain the shallow characters, the cliché story plots and even the bad walk cycles of the avatars that you are staring at for hours on end. Only then it dawned on us that video-games were essentially games! That’s why they were called video-games. All this amazing technology, the spectacular realtime rendering, the sophisticated artificial intelligence, the revolutionary non-linear story-telling and mind-boggling capacity for interaction were used only as a way to present dull sports-like games.

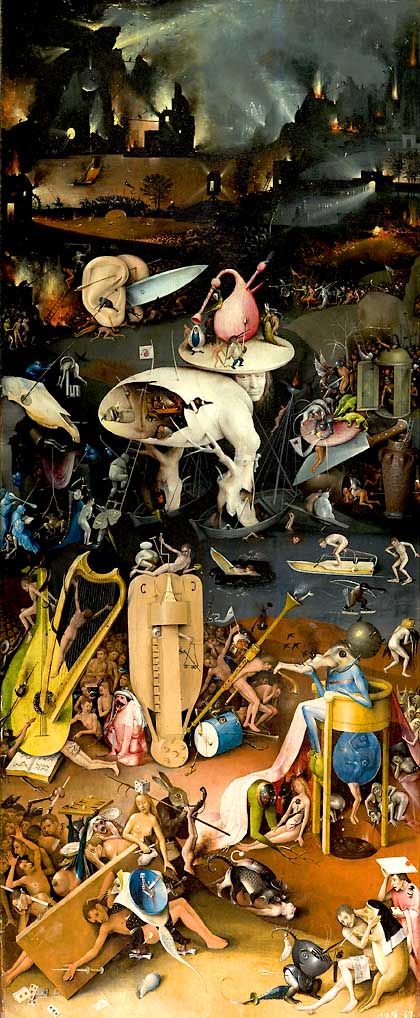

Playing these games was not about engaging with characters at all. It was about winning or losing. It wasn’t about exploration at all. It was about attaining goals. It wasn’t about having a good time. It was about getting rewards, getting results. We were dumb-founded. It was as if somebody took a big brush and scribbled a tic-tac-toe grid over Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. What a terrible waste of a perfectly fine medium!

What have people done to amuse themselves with computers since the CD-Rom era? Why hasn’t anyone made another Ceremony of Innocence since? What happened to the promise of exploration made by the first Tomb Raider? Why had people not realized that most of us were playing Myst for its world and its stories, and not the arcane puzzles? Why had developers continued to refine the simulation of fire arms rather than the immersion in virtual landscapes? And where does this damn loyalty to the 8-bit stone age come from?

I have no idea. Maybe it was easier to come up with rigid games than wrangle with wild fantasies. Maybe the technology was not accessible enough to artists. Maybe the industry was satisfied with its commercial results and reluctant to expand. Maybe the art world didn’t care enough.

I don’t know. But what I do know is that the desire is still there. We all know what we want from this medium, from the medium of video-games. We want it to deliver on the promise that art has been making for centuries. We want to visit other worlds, we want to walk in somebody else’s shoes, we want grasp a little bit of what it means to be in another situation. We want this medium to make our lives richer, our understanding of the world more intense, our connection to other people more profound. We want to live through adventures. We want to see the attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. We want to watch the C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate.

That is what video-games promise us on the back of the box. That is what gamers talk about when they reminisce their hours of playing. That is what excites non-gamers when they hear about this medium. We all like playing games just fine. But this is about something else! Something more! Something much more profound. This is not a game.

I’m delighted to see that, despite the setbacks of the previous decade, the first glimmers of hope have started to appear on the horizon of the video-games medium. That is what is presented in this exhibition. Video-games created by passionate people intent on exploring the potential of this new medium. Unsurprisingly, most of these have been created by independent developers, individuals or small teams working on shoestring budgets. It’s hard work. And we’re going against the grain. But we all believe that this work needs to be done. We owe it to this medium. And we owe it to humanity. We will find a way.

I would like to thank the Cologne GameLab for organizing this event and designing this truly wonderful exhibition. Maybe it will become historic. Maybe this will be the turning point. Maybe video-game developers and artists will respond to the wake up call. We have a wonderful new medium here, let’s make something with it!