In Mass Effect 2, you play the commander of a space ship on a mission to destroy an alien threat. Along the way, you collect team members of various species and genders. The performance of these characters depends in part on their feelings for you as a person. And this is where the game got interesting for me.

Even if there is a minor strategic advantage to winning the loyalty of your colleagues, their personalities are so outspoken that it is virtually impossible not play this on a more personal level. There’s certain characters you like more than others. There’s several you can imagine your commander being romantically attracted to. And the game does offer opportunity to pursue this. My commander Sheppard had a wonderful intimate encounter with an alien scientist called Tali, whose body was so susceptible to infection that she had to wear a space suit at all times. It was terribly romantic.

And it wasn’t just romance. There’s a lot of talking in Mass Effect. In a way, it feels like all of the interactions in the game are designed for the sake of narrative. That’s virtually unique in video games. The backstory to the game is rather dull and conventional, but it serves well as a backdrop for your relationships with the other characters, both on your ship and on alien planets. The entire game revolves around these relationships. Even the numerous shoot-outs don’t feel as much like game challenges (at least when played in easy mode) than they do like opportunities to bond with your team mates. For each mission, you chose two people to join you. With these two, you share the tediousness of the game, which adequately expresses the tediousness of the combat situation, tightening a bond between you, as a result of shared suffering.

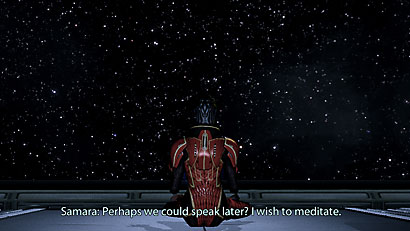

Each of the characters has a personal issue they need to resolve. You can decide to help them. And when you succeed, their friendship for you will increase. So success or failure of these missions feels much more important than in other games where failure often just means that you have to redo the mission until you get it right. Unlike in most video games, failure is a valid outcome of a mission in Mass Effect 2. And failure means that you have disappointed a friend. I guarantee that it hurts, when you’re really fond of someone and you fail to help them with a problem that was very important to them. I can never think of Samara without regret. When I see her meditating on the floor of her cabin, introverted, unwilling to talk to me. It hurts the way a virtual bullet never could.

It’s a heart warming experience to converse with the crew of your ship. Even if, and especially because, these interactions have no effect on the game’s outcome. You simply engage in them for their own sake. Flirting for the fun of it, sharing jokes or just looking out at the stars together. Friendly warmth in the freezing vacuum of space.

The depth of these relationships, is felt when choosing team members for particularly dangerous missions. There is no way that you can select your virtual lover to go on a suicide mission, even if she’s the most suitable for the job. It’s a strange sensation to be so attached to a character that your performance as a gamer becomes irrelevant. The kind of sensation that is really unique to this medium and that should be explored further and by more developers.

Because there’s still a few areas where the experience could be improved if developers radically choose to make their work about people, and not about objects and systems. For instance, your relationship with other characters only really develops on the ship. If you’re on a planet or in combat, your team members seem to have forgotten how close you two are (or not). Combat is all business. That’s a pity. Also, having shared a dangerous situation only emotionally effects you, the player. It doesn’t seem to change the feelings of the people you shared it with. It’s as if they forget the hardship as soon as they return to the ship.

Another inaccuracy is the fatality of decisions made in the course of a relationship. The game does not allow you to apologize or to clear up a misunderstanding. Any attempt to be friendly with a person after a conflict is futile. They will remain stubborn and sulking for the remainder of the game. Relationships also don’t evolve on their own. They just sit and wait for you to do something. On the one hand this contributes to the gravity of your decisions. But on the other, the rigidity of such a structure makes one unpleasantly aware of the hard computer logic that runs underneath the experience. It spoils the mood.

In the end, Mass Effect 2 is an exhilarating ride. Not because of its epic kitsch backstory, its combat with supernatural weapons or its Thunderbirds-are-go fetishism of futuristic machinery. But because it’s about people. And about relationships between people. Through the exploration of relationships with characters we are unlikely to encounter in real life, we can broaden our affective horizons. We are invited to deal with all sorts of exotic concerns, and learn about ourselves as we do. As such, Mass Effect 2 is an emotionally enriching experience, a shining example of the potential of video games as an expressive medium.